Abstract

-

Purpose

To validate the Korean version of the Attitudes towards Men in Nursing Questionnaire (K-AMnQ) using a sample of Korean nurses.

-

Methods

To measure the perceptions of male nurses, this study translated and adapted the AMnQ developed in India to the Korean context and collected data from 319 nurses. Item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, and confirmatory factor analysis were conducted on the collected data to verify convergent validity and discriminant validity, and the Korean version of the male nurse recognition scale was finalized with three factors and nine questions.

-

Results

The analysis showed that the scale had both validity and reliability.

-

Conclusion

This tool can be used to improve attitudes and interventions among male nurses.

-

Key Words: Nurses; Stereptyping; Validation study; Factor analysis

INTRODUCTION

1. Rationale for the Study

As of the 2023 national exam, the number of male nurses who passed the nursing licensure exam exceeds 30,000, accounting for 5% of the total licensed nurses [

1,

2]. Despite this increasing trend, male nurses continue to experience various biases in clinical settings. The biases identified in previous studies have been evident in interactions with colleagues and in providing patient care. Previous studies have confirmed that the general public holds perceptions about male nurses including biases such as assuming they have feminine or homosexual tendencies [

3], stereotypes that “nursing is a woman’s job,” concerns about gender-based differences in nursing performance, mistaking them for medical assistants or technicians [

4], and the bias that “male nurses won’t stay long” [

5]. Male nurses have reported experiencing issues such as “objections or rejections regarding their nursing performance or misunderstandings leading to inappropriate behavior”, “the perception of being scrutinized as a minority” [

4], “expectations related to traditional male roles outside of nursing” [

6], and “conflicts with younger but more experienced female nurses”[

7]. The experiences of rejection through these biases and gender stereotypes are related to the fact that many male nurses are assigned to specialized departments in hospitals, such as physician assistants (PA), emergency rooms, intensive care units, and operating rooms [

8]. Specialized departments offer advantages such as minimizing gender role biases and leveraging the physical strengths typically associated with men [

9]. However, they also present challenges, including a disconnect from undergraduate education, limited options for department selection, and restricted opportunities for direct patient care [

6]. Male nurses assigned to these specialized departments often experience uncertainty and ambiguity about their future, leading to ongoing concerns about their career paths [

10,

11].

In such situations, research on male nurses has primarily addressed biases from colleagues and patients, the image of nursing [

12], gender role stereotypes in nursing [

13,

14] and role conflicts [

15], Gender roles, professional image, and occupational expertise [

16]. These studies have often been discussed as secondary findings related to the imbalanced gender ratio in nursing. Given that research has generally been conducted with the assumption of a predominantly female nursing workforce, studies focusing on male nurses and nursing students are mostly phenomenological in nature. In the above research, while male nurses are evaluated as having relative strengths, such as physical endurance and strengths related to issues like childcare, common findings in existing phenomenological studies reveal that male nurses often grapple with concerns about future prospects, career vision, and tend to consider frequent job changes [

17]. Despite the increasing trend of male nurses, there is a need for metrics that can serve as indicators for creating and improving environments where they can thrive in clinical settings. However, research on the experiences and biases faced by male nurses is insufficient, and there is a lack of validated measurement tools that can be used to assess and improve these aspects.

Reviewing previous studies both domestically and internationally, in domestic research, Lee (1997) developed and utilized a tool to measure vocational perceptions of the nursing profession among male high school students [

18]. It was created through preliminary surveys with nursing students to measure perceptions of the nursing profession, career choice, roles, and values. In this study, the scale was used to measure perceptions of nursing as related to career choices among high school students. The items related to vocational perception consist of one domain with eight items.

In Canada, the Attitudes and Perceptions towards Men in Nursing Education (ATMINS) tool was proposed to compare social perceptions and attitudes towards male nurses. This scale consists of one factor with six items. However, the results of factor analysis were not presented, and there are limitations in validating the factor structure, as well as the tool’s validity and reliability. Additionally, the tool measures perceptions through the image of male nurses as portrayed in social perceptions and media, rather than focusing on personal perceptions and attitudes [

19].

Attitude towards Men in Nursing Questionnaire (AMnQ) is a tool developed in India by Sharma and Mudgal to measure attitudes and perceptions towards male nurses among nurses, nursing students, doctors, and patients. The tool was refined through a systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, resulting in an initial draft with 28 items. After validation of face and content validity by a panel of experts, exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted, leading to the final AMnQ, which consists of 15 sub-items across 3 factors. The tool has the advantage of a small number of items, making it easier for respondents to answer. Additionally, it is specifically designed to focus solely on male nurses, differentiating it from existing tools that typically measure perceptions and images of nurses in general, often categorizing male nurses as a sub-group within gender-related assessments [

20]. This distinguishes the AMnQ from previous studies that have measured the image of male nurses as a sub-factor of career choice and served as tools for assessing social perceptions, often without undergoing factor analysis and being presented as single-factor tools. The AMnQ is positively evaluated for its focused study on male nurses alone, utilizing systematic literature review and factor analysis to evaluate individual perceptions. Given the increasing diversity and complexity in clinical settings, it is important to examine the perceptions and evolving images of male nurses among colleagues and patients. Therefore, this study aims to validate the KAMnQ and introduce it to the domestic context, contributing to the clinical adaptation and expansion of diversity among male nurses.

The purpose of this study is to validate the reliability and validity of the Korean Version Attitudes towards Men in Nursing Questionnaire (K-AMnQ) for nurses in South Korea.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study is a methodological research aimed at translating the AMnQ, developed for measuring perceptions of male nurses, into Korean and validating its reliability and validity for use among nurses in South Korea.

2. Study Instruments

After reviewing previous studies, two comparative scales were selected to verify the construct validity of the current scale. These were chosen with the expectation that they would either show a correlation with the current scale or exhibit low or no correlation.

1) Attitude Towards Men in Nursing Questionnaire (AMnQ)

The AMnQ, developed to measure perceptions of male nurses, underwent a translation process with the author’s approval. Initially, it was translated by a bilingual nurse fluent in both Korean and English, who has experience living abroad. Subsequently, a reverse translation was carried out by a nursing student currently studying abroad, without providing the original text. The researcher and translators compared the original tool and items to ensure equivalence. The survey, which assessed respondents’ perceptions and attitudes towards the feminine characteristics and professionalism of nursing, empathy, and caregiving, was structured into 3 factors and 15 sub-items. The test-retest reliability of the completed scale for stability was Cronbach’s ⍺=.93, N=115. The reliability for each factor was Cronbach’s ⍺= .80, .88, .89, demonstrating excellent internal consistency. In this study, the reliability was Cronbach’s ⍺= .77. Based on this final scale, attitudes towards male nurses can be measured by summing the item scores, with a minimum total score of 15 and a maximum total score of 75. For negatively worded items, which are items from Factor 1 (items 1~7) and Factor 3 (items 12~15), reverse scoring is applied.

2) Revised Korean Gender Egalitarianism Scale (KGES)

The tool was developed as a condensed version of the Revised Korean Gender Egalitarianism Scale (2019) to enhance user accessibility and convenience. It consists of a total of 12 items, with 2 items per factor across 6 factors, using a 4-point Likert scale. In the condensed version, Item 9 is a positively-worded question that is reverse-coded. Total scores range from 12 to 48, with lower scores indicating higher gender egalitarianism. The reliability coefficient in the original study was Cronbach’s ⍺=.87, while in this study, the reliability coefficient is Cronbach’s ⍺=.71 [

21].

3) Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (RSES)

The scales were selected as tools to verify discriminant validity. The scales used in this study were those that had undergone retranslation and validation processes by Lee et al., and were used with the author's approval [

22]. The tool is a single-factor measure using a 4-point Likert scale, with reverse scoring applied to negatively worded items. Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem, with scores above 30 considered as "healthy and desirable self-esteem." In the referenced study, the reliability coefficient was Cronbach’s ⍺=.81 to .89, while in this study, the reliability was Cronbach’s ⍺=.68.

The participants in this study were nurses from a specific region who consented to participate and completed the survey. There are various opinions among scholars regarding the minimum sample size; for exploratory factor analysis, a minimum sample size is recommended to be at least five times the number of items [

23], and for confirmatory factor analysis, a minimum of 150 samples is advised [

24]. For factor analysis, the number of participants was set at 300, considering a dropout rate of 10%, resulting in a total of 330 surveys distributed. Data collection was conducted from July 1, 2023, to October 31, 2023, via mobile links and paper surveys. Of the 319 valid responses received, 100 were used for exploratory factor analysis, and 219 were used for confirmatory factor analysis.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. 1041386-202301-HR-10-02). Online and offline surveys were collected anonymously, and responses containing personal information were kept confidential. Participants were informed that they could freely withdraw from the study. Procedures for the use and termination of personal information were disclosed, and responses were coded to ensure that individuals could not be identified. Files were password-protected, and surveys were stored in a secure, locked location. Participants received tokens of appreciation for their participation. Data will be securely stored for 3 years after the conclusion of the study, after which it will be permanently deleted and disposed of.

5. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using IBM SPSS/WIN 27.0 and AMOS 27. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the general characteristics of the participants. To verify construct validity, item analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted to explore and restructure the factors of the original tool. In the case of the original tool model, a 3-factor, 15-item structure was established. However, considering social and cultural differences, variations in sample groups, and differences in organizational culture and work environments, directly translating foreign tools into the domestic context does not guarantee validity and reliability. Therefore, exploratory factor analysis was performed [

25]. This was then verified through confirmatory factor analysis, with exploratory factor analysis using Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin’s measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (25), and confirmatory factor analysis using absolute fit indices such as Standard Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and incremental fit indices including Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) [

26].

The assessment of convergent validity was conducted using Standardized Regression Weights, β (SRW, β) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values. Typically, a value of 0.50 or higher is considered indicative of convergent validity. This means that at least 50% of the variance in the items should be explained by the construct [

27-

29]. For discriminant validity of the items, we followed the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker [

28], where the AVE of a specific latent variable should be greater than the squared correlations between that latent variable and other latent variables to be considered satisfactory. Convergent and discriminant validity were assessed by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients, while reliability was evaluated using Composite Reliability and Cronbach’s ⍺.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Participants

Among the study participants, 300 (94%) were female respondents. In terms of work settings, 61.8% worked in general wards, 13.2% in specialized departments such as intensive care units, emergency rooms, and operating rooms, 5.6% in outpatient departments, and 19.4% in other areas such as procedure rooms, laboratories, and PA. Among the participants, 80.6% reported having experience working with male nurses, and 60.8% indicated that they have male nurses or nursing students among their family members or relatives. Additionally, 88.1% of the participants reported having attended classes with male nursing students, and 95.9% stated that they had seen male nurses or nursing students in the media. Among those who had experienced hospitalization, 22.7% reported having received care from male nurses (

Table 1).

As the first step in item analysis, the mean and standard deviation of each item were reviewed, and the skewness and kurtosis of each item were examined to assess the normality of the data for structural equation modeling. The skewness value of the analyzed data was -.052 and the kurtosis value was .180. Since the absolute value of skewness should not exceed 2 and the absolute value of kurtosis should not exceed 10 [

30], the assumption of normality was satisfied.

Next, the Item-Total Correlation (ITC) was examined to assess the contribution of each item and the homogeneity of the scale. Item correlations with a magnitude less than 0.2 were considered to have low discriminative power, while correlations between .20 and .30 were deemed acceptable [

31,

32]. Items 8 and 9, which were evaluated as having low discriminative power, were deleted. The remaining items showed correlations ranging from .290~.545 with the total scale, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency (

Table 2).

1) Exploratory factor analysis

The KMO value was 0.82, which indicates that the selection of variables for factor analysis was quite good. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity showed a x

2=1,129.116 (

p<.001), confirming that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Through Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation for factor extraction, item 10 with a factor loading less than .04 was excluded, resulting in a revised structure with 3 factors and 12 items (

Table 2).

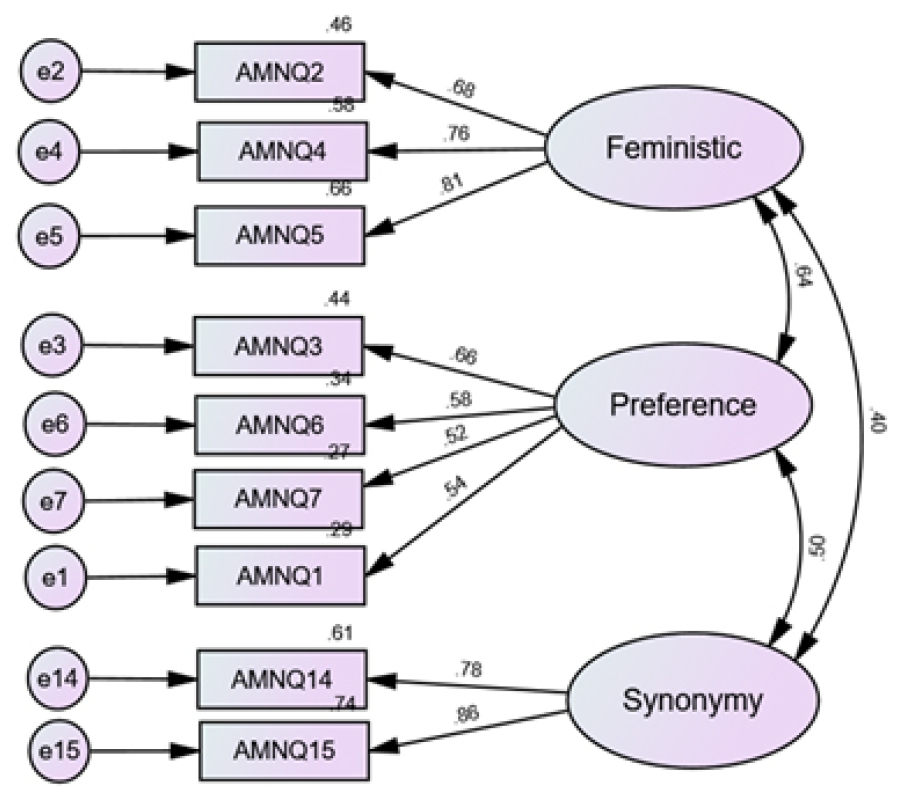

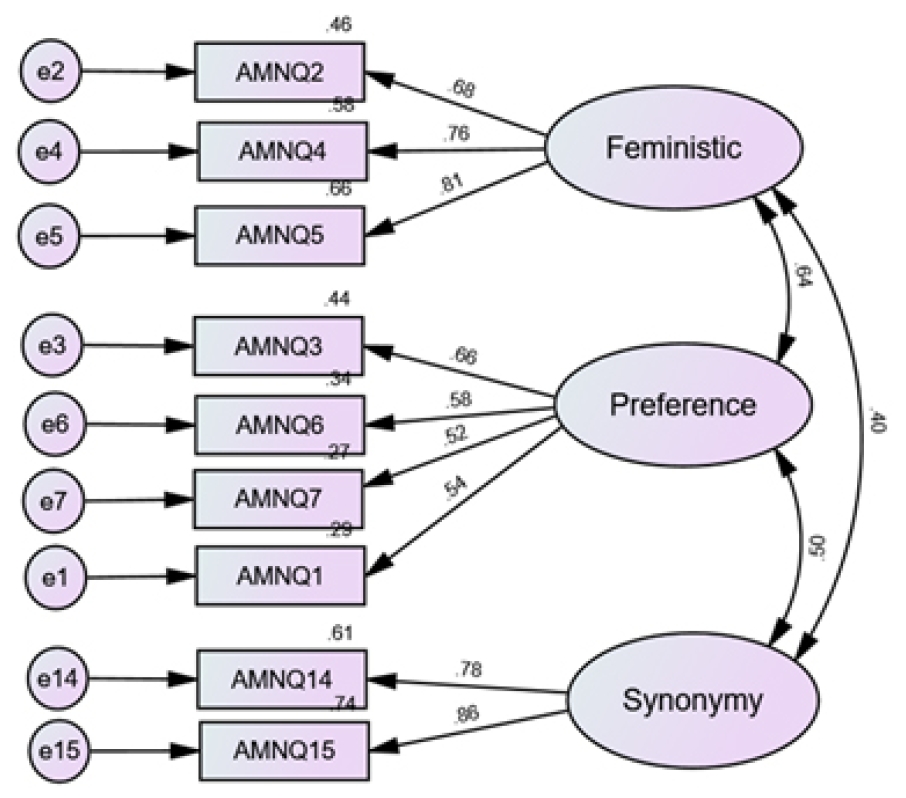

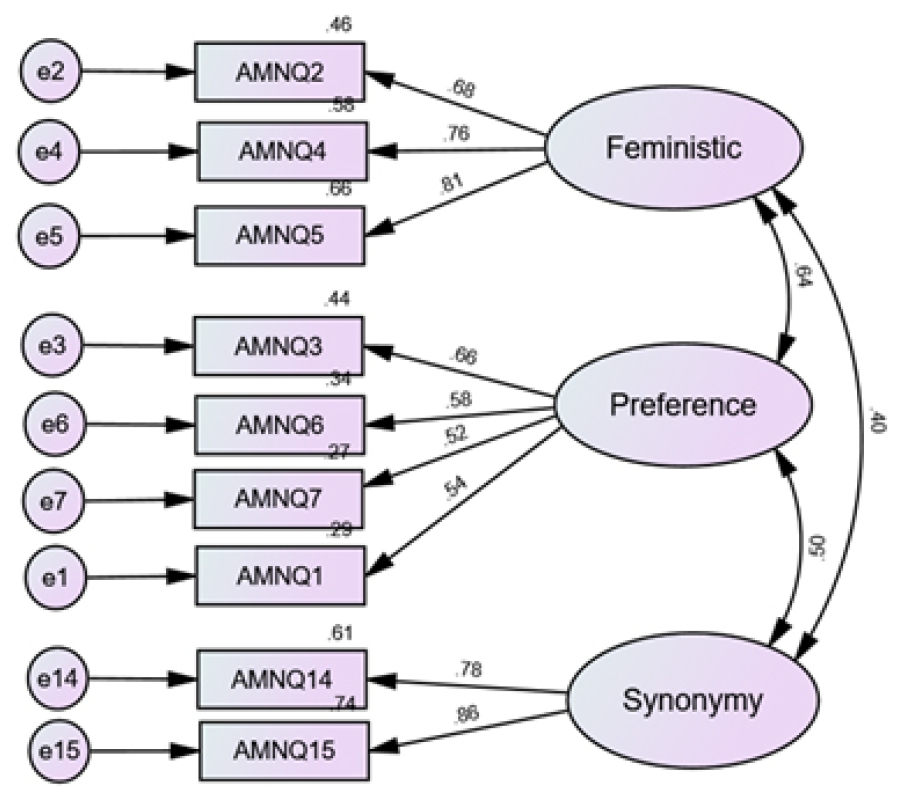

2) Confirmatory factor analysis

After conducting Exploratory Factor Analysis, Confirmatory Factor Analysis using structural equation modeling was performed to assess the model fit for the three-factor structure of the K-AMnQ. Since the assumption of normality was satisfied in the item analysis, estimation was conducted using Maximum Likelihood, and the fit of the variance structure model was evaluated through various fit indices.

RMSEA and SRMR indicate the overall model fit. In this study, the RMSEA value is 0.08. The acceptance criterion is below 0.1, and a value below .08 is considered to indicate an excellent model fit. Unlike other fit indices, SRMR is useful because it does not depend on model complexity. Values below .05 are considered acceptable, and lower values indicate a better model fit. In this study, the SRMR was 0.493 [

33]. Among the incremental fit indices, TLI and CFI indicate the degree of improvement of the model. Values above .90 are considered to demonstrate excellent fit [

34]. In this study, the CFI value was 0.937 and the TLI value was 0.905, indicating that the measurement model is deemed adequate (

Figure 1).

3) Convergent and discriminant validity

The results of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis were used to assess the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the structural validity. Items 11, 12, and 13, which had standardized factor loadings of less than .50, were removed. There were no Heywood cases, where error terms are estimated as negative values, and convergent validity was confirmed.

Discriminant validity was assessed according to the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker [

28], which involves comparing AVE with the squared correlations between each factor. The analysis was conducted to ensure that the AVE for each factor was greater than the squared value of the highest correlation between any two factors. The AVE values were confirmed as follows: Feministic is .56, Preference is .67, and Synonymy is .67. For Feministic and Preference, the squared factor correlations were larger than the AVE values, indicating that the two factors could not be easily distinguished. Using the same method to analyze the discriminant validity between other factors, it was found that Preference and Synonymy demonstrated partial discriminant validity, while Feministic and Synonymy met the discriminant validity criterion, as the squared factor correlations were smaller than the AVE values [

27,

28] (

Table 3).

1) Convergent validity

To validate convergent validity, Pearson correlation tests were conducted between K-AMnQ and KGES. The two scales were hypothesized to exhibit a correlation based on a review of existing literature. As a result, the correlation coefficient between K-AMnQ and KGES was r=.304 (

p<.001), confirming convergent validity.[

35,

36].

2) Discriminant validity

To assess discriminant validity, the hypothesis is that the measure being validated in this study should have little to no correlation with other scale. If this hypothesis is confirmed, then discriminant validity is considered to be established. In this study, the RSES was selected as a comparative measure. In this study, the correlation between K-AMnQ and RSES was analyzed using Pearson correlation tests. The correlation analysis resulted in r=.067. The analysis demonstrated that the concept is distinct and has no significant correlation, thus confirming discriminant validity.

5. Reliability

The internal consistency reliability for the three factors of the K-AMnQ is Cronbach’s ⍺=.775. It was confirmed that there is a positive correlation among all domains. The Composit Reliability of the validation model was 0.892, which is above 0.7, indicating that the construct validity is considered good [

24].

DISCUSSION

The present study commenced with the intention of clarifying existing biases and perceptions towards male nurses. As of 2023, male nurses constitute only 5% of the total nursing workforce but are on a steady upward trend. Studies on how patients, fellow nurses, and medical staff perceive and stereotype male nurses’ roles have often been discussed tangentially in research measuring traditional gender stereotypes, gender roles, biases, and images. Preceding phenomenological studies have reflected on the concerns and biases faced by male nurses, scrutinizing the limitations of existing scales measuring perceptions, images, and fixed gender role stereotypes of nurses in South Korea.

Following this groundwork, the AMnQ tool developed by Sharma and Mudgal [

20] in India to measure perceptions of male nurses has been validated for introduction in Korea. This scale was developed to address social changes related to the increasing number of male nurses in India and to point out the absence of an objective perception scale for male nurses. Through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, the scale has been finalized with three factors and 15 sub-items. The study included translation and back-translation of the original tool to ensure equivalence and presented the Korean version of AMnQ. Detailed analyses were conducted to validate item properties, structural validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct validity of the Korean AMnQ.

Through item analysis, the normality of the data was verified, and item-total correlations were assessed. Based on this evaluation, items 8 and 9, which were deemed to have low discriminative power, were removed to ensure internal consistency. The original tool model established a three-factor structure; however, due to differences in sample populations, organizational culture, and work environments, simply translating and adopting a foreign tool may not guarantee validity. Therefore, the existing factor structure was excluded, and exploratory factor analysis was conducted. In this process, the KMO value was 0.82, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded x

2=1,129.116 (

p<.001) [

25], which was significant. Based on this, principal component analysis with Varimax rotation was performed to extract factors, excluding item 10 with a factor loading less than .04, resulting in a revised model with three factors and 12 items.

Next, to assess model fit, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted, and fit indices were reviewed. The results confirmed excellent model fit and the degree of improvement in the research model, demonstrating that the model is acceptable [

33].

Item convergent validity refers to the internal consistency and explanatory power among the measurement variables within each factor. Using the results from confirmatory factor analysis, SRW and AVE were examined, and items 11, 12, and 13, which had SRW values below .50 and were deemed to lack explanatory power, were removed. Item discriminant validity involves evaluating the overlap, similarity, or distinctiveness of concepts between two or more factors. This assesses whether items in one factor are sufficiently distinct from items in other factors.

To verify discriminant validity according to the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker [

28], the squared correlations between the largest factors were compared with AVE. For Feministic and Preference, the squared correlation exceeded the AVE, suggesting that these two domains are difficult to distinguish from each other. When analyzing discriminant validity between other factors using the same method, Preference and Synonymy met partial discriminant validity criteria. Additionally, Feministic and Synonymy had squared factor correlation values smaller than the AVE, indicating that discriminant validity was satisfied. The fact that 95% of all nurses are female cannot be considered unrelated to the validity verification results mentioned above. Despite the increasing trend of male nurses, they remain a minority and have reported experiences related to gender stereotypes, such as the perception of “nursing as a female profession” [

4]. The images of nurses associated with gender roles [

12], and the presence of stereotypes also reflect that many participants expressed a sense of disconnect between being male and working as a nurse. Given these factors, it is understandable that there is considerable overlap and high similarity between the factors of Feministic and Preference. However, in contrast to the previous two factors, Synonymy consists of items that measure the equality of nurses of different genders. Therefore, it is interpreted as having distinct characteristics and being differentiated from the other two factors. Even if the AVE value is below .50, if the CR value is .60 or above, it can still be considered acceptable [37]. Therefore, overall, it can be said that partial discriminant validity is demonstrated. An approach that emphasizes internal consistency of the entire model is often used in both practice and research. Considering the situation described, it is advisable to interpret the results by taking other indicators into account as well. Therefore, it can be regarded as acceptable [

28].

To confirm the construct validity, we verified convergent validity by analyzing the positive correlation with the gender equality measurement tool, KGES. The analysis demonstrated that the concept is distinct from the self-esteem measurement tool, RSES, as there was no correlation, thereby confirming discriminant validity. The reliability of the measurement tool was assessed with a Cronbach’s ⍺=.77, indicating a positive correlation among all items. Additionally, the Composite Reliability was .89, which is above the threshold of 0.7, suggesting that the convergent validity is good [

24].

The Korean version of the AMnQ, as presented, consists of a total of 9 self-report items with verified structural validity and reliability. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The factors have been named as Feministic, Preference, and Synonymy. While these names are similar to those in existing tools, the second factor underwent validation and showed variations in its sub-items, leading to the current naming. This can be interpreted as a difference in factor structure due to cultural variations. The first factor consists of 3 items that measure the feminine aspects of nursing. The second factor consists of 4 items that measure preferences arising from the gender of male and female nurses. The third factor is comprised of 2 items that assess the equality between male and female nurses. In the original scale, 4 sub-items from the second factor and 2 items from the third factor were removed.

From the collected data, it was found that 80.6% of the respondents in this study reported having experience working with male nurses. The proportion of respondents who reported having male nurses or nursing students among their family or relatives was also 60.8%. Additionally, 88.1% of respondents reported having attended classes with male nursing students, and 95.9% stated that they had seen male nurses or nursing students in the media, with both proportions exceeding the majority.

In contrast, 94% of the respondents are female nurses. Among those who reported having hospitalization experience, only 22.7% indicated that they received care from a male nurse. This finding aligns with the current proportion of male nurses, who make up about 5% of licensed nurses [

1]. The small proportion of male nurses working in hospital wards is consistent with previous research findings. However, the higher frequency of exposure to male nurses in the media, clinical settings, and educational environments suggests that their significance and impact are considerable and should not be underestimated.

This scale can serve as a tool to assess the perceptions of male nurses and to measure potential strategies for improving these perceptions. Existing scales related to nurse perceptions were not specifically developed to measure the perceptions of male nurses. Therefore, to address and understand issues such as gender role stereotypes, role conflicts, and professional image, various methods are utilized. This includes measuring conflicts experienced by male nurses through qualitative research [38], interviews, and statements. Such diversity in approach can be understood as an effort to address the limitations of existing scales and to better capture and address the unique challenges faced by male nurses. In particular, most research focused on male nurses [

3-

15]primarily involves analyzing differences between male and female nurses, identifying conflict situations, and examining negative perceptions and images among patients. In this context, it is important to note that this scale functions as a fundamental measurement tool before proposing various strategies for improving perceptions. In Korea, this study is significant as it presents the first perception measurement tool specifically targeting male nurses and has undergone factor analysis, reliability, and validity testing. It is expected that this tool will be actively utilized in future research focusing on male nurses. However, this study is limited by its focus on nurses from a single region, which means it did not include a diverse range of participants. Due to the biased sampling of clinical nurses, caution is needed when generalizing the results. It is suggested that future research should involve validation of measurement tools across different groups, including nurses, the general public, patients, and healthcare professionals, as well as conducting repeated studies to address these limitations.

CONCLUSION

This study measured the perceptions of male nurses in response to their increasing numbers and provided a foundational tool for intervention. The AMnQ, developed in India, was translated to fit the Korean context, and the K-AMnQ was presented as a self-report measurement tool with a 5-point likert scale. This tool was validated through reliability testing, construct validity verification, and factor analysis, resulting in a 9-item scale across 3 factors, based on a sample of 319 nurses from a specific region. By confirming both convergent and discriminant validity with other scales, this study enables the quantitative measurement of male nurses’ perceptions. It contributes to the advancement of future research aimed at improving these perceptions and ultimately supports the enhancement of positive perceptions and environments for male nurses. This, in turn, can help foster greater diversity in clinical settings and contribute to the overall improvement of the healthcare environment.

Figure 1.Framework of confirmatory factor analysis of the Korean-translated version of the attitudes towards men in nursing questionnaire [K-AMnQ].

Table 1.Characteristics of Participants (N=319)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) or M±SD |

|

Gender |

F |

300 (94.0) |

|

M |

19 (6.0) |

|

Clinical career (yr) |

<1 |

16 (5.0) |

|

1≤,<5 |

96 (30.1) |

|

5≤,<10 |

91 (28.5) |

|

10≤ |

116 (36.4) |

|

Department |

Ward |

197 (61.8) |

|

Special part (ICU, ER, OR) |

42 (13.2) |

|

OPD |

18 (5.6) |

|

ETC (Center, IRC, PA) |

62 (19.4) |

|

Presence of male nurses in the department |

Yes |

257 (80.6) |

|

No |

62 (19.4) |

|

Presence of male nurses in the family |

Yes |

194 (60.8) |

|

No |

125 (39.2) |

|

Hospitalization experience |

Yes |

176 (55.2) |

|

No |

143 (44.8) |

|

Experience of being cared for by a male nurse |

Yes |

40 (22.7) |

|

No |

133 (77.3) |

|

The experience of taking a class with a male nursing student |

Yes |

281 (88.1) |

|

No |

38 (11.9) |

|

Experience of seeing a male nurse in the media |

Yes |

306 (95.9) |

|

No |

13 (4.1) |

Table 2.Exploratory Factor Analysis (N=100)

|

Factors |

Items |

ITC |

Factor-loading |

|

r |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Feministic |

2. Nursing is suitable only for the females |

.49 |

.69 |

|

|

|

4. Nursing is considered as low-level occupation for the males |

.54 |

.77 |

|

|

|

5. Nursing is considered as purely a female profession |

.47 |

.84 |

|

|

|

Preference |

1. People prefer to be cared by female nurses only |

.42 |

|

.78 |

|

|

3. Male patients also prefer to be cared by the female nurses only |

.52 |

|

.63 |

|

|

6. Hospitals prefer to appoint female nurses |

.41 |

|

.57 |

|

|

7. Nursing is very challenging and frustrating occupation for males |

.42 |

|

.47 |

|

|

11. Male nurses are more suitable for some of the hospital units such as psychiatry, emergency, Operation Theater, and critical care units |

.29 |

|

.41 |

|

|

13. Female patients do not prefer to be cared by male nurses |

.34 |

|

.56 |

|

|

Synonymy |

12. People do not prefer to send males for the nursing profession |

.47 |

|

|

.58 |

|

14. Female nurses are more caring and tender heart than male nurses |

.50 |

|

|

.82 |

|

15. Female nurses are more polite and courteous in patient care |

.54 |

|

|

.81 |

|

Eigen value |

|

|

2.44 |

2.30 |

2.16 |

|

Explained variance [%] |

|

|

18.7 |

17.7 |

16.6 |

|

Cronbach’s ⍺ |

.723 |

|

.789 |

.467 |

.734 |

Table 3.Fornell-Larcker Test for Discriminant Validity

|

Variables |

CR |

AVE |

Feministic |

Preference |

Synomymy |

|

Feministic |

.79 |

.56 |

1 |

|

|

|

Preference |

.66 |

.33 |

.64 |

1 |

|

|

Synonymy |

.80 |

.67 |

.40 |

.49 |

1 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Jeong GS. More than 30,000 male nurses --- 3,769 new nurses will be released by the national government this year. The Korean Nursing Association News. 2023 February 17; Sect. 01.

- 2. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Health and Welfare Statistical Yearbook 2023. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

- 3. McMillian J, Morgan SA, Ament P. Acceptance of male registered nurses by female registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2006;38(1):100-106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2006.00066.x

- 4. Ahn KH, Seo JM, Hwang SK. Content analysis of male hospital nurses’ experiences. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2009;21(6):652-665.

- 5. Suh YO, Lee KW. Female peer nurse’s experiences working with the male nurses. Journal of East-West Nursing Research. 2017;23:(1):https://doi.org/10.14370/jewnr.2017.23.1.33

- 6. Son HM, Koh MH, Kim CM, Moon JH, Yi MS. The male nurses' experiences of adaptation in clinical setting. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2003;33(1):17-25. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2003.33.1.17

- 7. Kim MY. An exploratory study of masculinity in nursing. Journal of Korean Clinical nursing research. 2009;15(2):37-46.

- 8. Choi JH, Jang CH, KIM SS. The effects of the gender role identity and gender stereotypes on the prejudice against male nurses of hospital workers. The Korea Contents Association. 2018;18(12):75-91. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2018.18.12.075

- 9. Egeland JW, Brown JS. Men in nursing: Their fields of employment, preferred fields of practice, and role strain. Health Services Research. 1989;24(5):693-707.

- 10. Yu M, Kang KJ, Yu SJ, Park MS. Factors affecting retention intention of male nurses working healthcare institution in korea. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2017;23(3):280-289. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2017.23.3.280

- 11. Hong JY, KIM SN, Ju MJ, Sohn SK. The experience of male nurses working in intensive care units. Journal of Korean Clinical Nursing Research. 2020;26(3):352-364. https://doi.org/10.22650/JKCNR.2020.26.3.352

- 12. Kim HJ, Kim HO. A study on image of the nurse. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration. 2001;7(1):97-110.

- 13. Tak JK. Occupational sex stereotypes among korean college students: Differences based on sex, sex-role type, and culture. Korea Journal of Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 1995;1995(1):437-447.

- 14. Park HS, Ha JH, Lee MH. The relationship among gender-role identity, gender stereotype, job satisfaction and turnover intention of male nurses. Journal of the Korea Academia-Industrial cooperation Society. 2014;15(5):2962-2970. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2014.15.5.2962

- 15. Han JE, Park NH, Cho JH. Influence of gender role conflict, resilience, and nursing organizational culture on nursing work performance among clinical nurses. The Journal of Korean Academic Society of Nursing Education. 2020;26(3):248-258. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2020.26.3.248

- 16. Yeun EJ, Kwon YM, Ahn OH. Development of a nursing professional values scale. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2005;35(6):1091-1100. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2005.35.6.1091

- 17. Lee YS. Effects of work-family conflicts and workplace support, on the mental and physical health of married nurses [master’s thesis]. Cheonan: Dankook University; 2013.

- 18. Lee JH. Male High School Student’s Perception of Nursing as a Career Choice [Master's thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 1997.

- 19. Bartfay WJ, Bartfay E, Clow KA, Wu T. Attitudes and perceptions towards men in nursing education. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2010;8:(2):6. https://doi.org/10.46743/1540-580x/2010.1290

- 20. Sharma SK, Mudgal SK. Development and validation of a scale to measure attitude of people toward men in nursing profession. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021;10:(1):54. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_530_20

- 21. Lee SY, Kim IS, Ko JH. Development of a revised Korean gender egalitarianism scale (II): Confirmation of items, standardization and a manual development. Seoul: Korean Women's Development Institute; 2019.

- 22. Lee JY, Na SK, Choi BY, Lee JH, Park YM, Lee SM. Errors in item translation of psychological assessmentby cultural discrepancy: Revising 8th itemof rosenberg’s self-esteem scale. Korea Journal of Counseling. 2009;10(3):1345-1358. https://doi.org/10.15703/kjc.10.3.200909.1345

- 23. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 5th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education; 2007. 504 p.

- 24. Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull. 1988;103(3):411-423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- 25. Kang HC. A guide on the use of factor analysis in the assessment of construct validity. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2013;43(5):587-94. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.5.587

- 26. Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- 27. Woo JS. The concept and understanding of structural equation modeling. Rev ed. Seoul: Hannare; 2022.

- 28. Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981;18(1):39-50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- 29. Lee HS, Im JH. Structural equation modeling with AMOS 16. Paju: Bubmunsa; 2009.

- 30. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

- 31. Sung TJ. Easy-to-understand statistical analysis using SPSS/ AMOS. 2nd ed. Seoul: Hakgisa; 2017.

- 32. Kline P. A handbook of test construction: Introduction to psychometric design. London: Routledge; 1986.

- 33. Hong SH. The criteria for selecting appropriate fit indices in structural equation modeling and their rationales. Korean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2000;19(1):161-177.

- 34. Kim D. Amos A to Z: Structural equation modeling analysis. Paju: Yspub; 2008.

- 35. de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, Knol DL. Measurement in medicine: A practical guide. Practical guides to biostatistics and epidemiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- 36. Lee J, Lee E-H, Chae D, Kim C-J. Patient-reported outcome measures for diabetes self-care: A systematic review of measurement properties. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2020;105:103498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103498